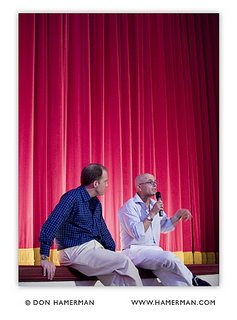

Seymour Cassel, the distinctive character actor boasting close to two hundred film and TV credits over a forty year career, will appear at the Avon Theatre in Stamford on Monday, October 23rd at 7:30 PM, to pay tribute to his friend and mentor, the late actor/director John Cassavetes. The Avon will screen Cassavetes’ ground-breaking 1968 film, “Faces”, which features Cassel. As a co-founder of the Avon, I had the pleasure of catching up with Seymour in advance. A summary of our conversation follows.

It seems the inimitable Seymour Cassel was born with greasepaint in his veins.

“My mother worked in the old Minsky’s troupe, which toured the country in the golden age of burlesque theatre,” Seymour recalls. “Of course she took me with her everywhere. As a kid, I remember wearing a checkered suit and appearing on-stage in the routines worked out by the “baggy pants” comedians. Mostly, I made their pants come down.”

In the artistically vibrant New York City of the fifties, Cassel was an acting student with the famed Stella Adler when he encountered an electric aspiring film-maker named John Cassavetes, just six years his senior. The two men clicked immediately, and from then on, both professionally and personally, Seymour never left John for very long.

Cassel sums up his feelings this way: “He was my dearest friend, and also the greatest director you could work with as an actor, because he always put the characters first. He understood that the nuances in a film existed as much in the actor as in the script. In fact, most often the camera and lighting people just had to keep up with what was unfolding in front of them. Ultimately, John cared less about whether a shot ended up in soft focus, more about whether the interaction in the scene had that ring of truth.”

The best way to experience what Cassel means is to lay your hands on The Criterion Collection’s indispensable box set, “John Cassavetes: Five Films” (2004), which features the director’s first experimental full-length film, “Shadows” (1959), his break-through feature, “Faces” (1968), followed by “A Woman Under The Influence” (1974), “The Killing Of A Chinese Bookie” (1976), and finally, “Opening Night” (1977). These titles comprise an inspired assemblage of the director’s best output.

Ahead of its time, “Shadows” centers on a fragile love affair which dissolves when a young white man discovers his naive girlfriend is half-black. In “Faces”, we follow the crumbling world of a middle-aged businessman (John Marley), who leaves his empty marriage and retreats to his mistress, a high-class call girl (Gena Rowlands). Meanwhile Marley’s wife (Lynn Carlin) finds solace with a kooky hustler played by Seymour. “A Woman Under The Influence” concerns a loving married couple (Rowlands and Peter Falk), who nevertheless can’t fully connect or understand each other, a problem aggravated when Gena’s character suffers a nervous breakdown. “Killing”, perhaps the most conventional of the series, is a flavorful gangster picture, as strip-club operator Ben Gazzara gets in over his head with the mob (including Seymour), while “Opening Night” shows stage diva Rowlands blocked over a part that suggests her advancing age.

Atypical of Hollywood and Hollywood couples, Cassavetes and Rowlands were married for thirty-five years (right up to his death), and made ten pictures together. For those who associate the actress with lighter, more recent fare- be it Lasse Hallstrom’s “Something To Talk About” (1995) or even “The Notebook” (2001, directed by son Nick), watching Rowlands in “Faces”, “Influence”, and “Opening Night” is a revelation. Across the board, she is riveting- a truly astonishing screen actress, with her gifts in full bloom playing her husband’s muse.

Always limiting the breadth of Cassavetes’ public was that none of his features were intended as pure entertainment. (Notably, the director once described his films as being about “love-and the lack of it”, a sobering issue if ever there was one.) Yet regardless of audience size (never his primary concern), John’s hard-won independence meant he could practice film-making as an authentic means of artistic expression, bypassing the culture of greed that corrupts so many mainstream movies.

A Cassavetes film usually makes the viewer a bit uncomfortable, like someone who’s walked into a party uninvited, one which could turn ugly any second. Such is the impact of the “truth” Cassavetes empowered his actors to find, reflecting life as a wondrously weird, often messy phenomenon.

Cassel observes: “John was intrigued by the contradictions in people. Say you love a woman, but over time little things start to bug you about her. So one day you start an affair. But you still love the other woman. You feel guilty, but you continue cheating. Is it to punish her or yourself? Why does this happen? John recognized that life was often very frustrating, and he was fascinated by the complexity of human behavior.”

Seymour elaborates further: “Central to John’s belief was the idea that people tend to talk at each other, not to each other”, creating a round-about dance where thorny issues of real significance get submerged, becoming invisible land-mines just waiting to be stepped on.

Though the rawness and immediacy of a Cassavetes film can be unnerving to watch, most always there’s a leavening effect. We witness light-hearted, loving moments. And we feel sympathy, even affection for many of his characters. Our hearts break for the deflowered girl in “Shadows”, the bewildered housewife in “Influence”, even the two-bit gambler in “Killing”, whose only home is his strip-club, his only family its sleazy denizens.

Cassavetes merits hero status among independent film-makers as someone who consistently found ways to fund his own films. “John could work no other way”, Seymour says simply. “He wanted that independence, because he truly loved making movies his way. There was noone I ever met who loved films and film-making more than John. He would often do commercial work, but this was mostly to fund his own productions. It was economic necessity, pure and simple.”

Clearly the two earliest films in the Cassavetes box set hold special significance for Cassel. On “Shadows”, where he’s billed as Associate Producer, Seymour first learned, in his words, “how to unscrew a camera from a tripod.” With John deploying him everywhere, the young actor gradually discovered how films were made, by observing and by doing. With “Faces”, Seymour notes, “we set in place the working method which would guide the rest of John’s films, including, to the best of our ability, shooting films in sequence.” This was done to let characters’ emotions build naturally.

Seymour volunteers this warm recollection: “When John was cutting “Faces”, he was really excited. He had the high emotions of his Greek heritage, and he turned to me one day and said, ‘Sey, you’re going to win the Oscar for this part!’ Of course I didn’t believe him.” (It turned out John’s wild prediction was extremely close to the mark: while Cassel didn’t win the Oscar, he was indeed nominated, along with co-star Lynn Carlin.)

In the late sixties, Cassavetes contracted hepatitis on a film set in Mexico, and was told by doctors that drinking alcohol would be risky to his long-term health. Yet as Seymour puts it, “Now and then John liked a cocktail, and sometimes he, Ben, Peter, and I would go out for a drink or two.” He adds softly, “We had a lot of fun.”

John Cassavetes died of a liver ailment just shy of his sixtieth birthday in 1989, but in the end, he was proud of the film legacy he’d built. Cassel comments: “John believed he’d done something special with his work, something that would live on after him.” And as his loving friend and collaborator Seymour Cassel would doubtless agree, he was right.

-John Farr

Post-script: my three favorite non-Cassavetes films featuring Seymour Cassel: Barry Levinson’s “Tin Men” (1987), Wes Anderson’s “Rushmore” (1998), and Billy Crystal’s “61*” (2001).

For these and other top DVD titles, visit

www.bestmoviesbyfarr.com.